Guest blogger: Adrian Slatcher, Life Online Advisory Panel Member

In 1998 I had just completed an M.A. in creative writing at the University of Manchester. I had a decent computer running Windows 3.11 and had invested one hundred and fifty quid in a modem which necessitated running a second phone line into the bedroom of my shared house, taking care only to go online when the rest of the house didn't need the phone. If you wanted to get in touch with me (I gave out my email address on the photocopied short story magazine I gave out to friends), then 101456.1226@compuserve.com was all you needed to remember.

It would be a couple of years before I watched live TV on the internet (on September 11th 2001 to be accurate), and downloading a photograph or an MP3 file was painfully slow. However, text was different. I'd not yet made my own web-page, but I knew you could, and besides, there were plenty of great online resources for writers.

I can't remember how I found out about the online writers' group run by Francis Ford Coppola's Zoetrope studios, but when I did I became addicted to it. Years before Web 2.0 and social media, here was a user-generated lit-crit site, free to join, and with an active, vociferous user base of real writers, albeit mostly in the USA and Canada. Coppola's films have regularly come from books (S.E. Hinton, Mario Puzo and Joseph Conrad amongst them) and his support for the short form, via this and the All-Story magazine were not without self-interest.

For the writers it was great. You critiqued a few stories with a few lines, and that gave you enough credit to upload your own story. I must have read two hundred stories during my few months on the site. Every month there was a competition, with the top rated stories going through to be read by an agent or something. Yet, years before Klout and record-breaking headcounts of Facebook friends or Twitter followers, the group dynamics of the web were already in play.

Some writers were vociferous joiners, frienders, whatever. They had their own clique who extravagantly praised everything they wrote, and they presumably returned the compliment. Around these Ashton Kutcher-like stars of the late 20th century online world, little satellites of like minded writers buzzed in there own mini-ecosystems. If only Google+ circles had been available to us then! I had my own little coterie, writers I liked and who liked my work – and I'd get home from work to see if anyone had responded to the story I'd put online late the night before.

Occasionally, in the forum someone would set a challenge, such as "let's all write a story with a character named Marvin in the title." At some point – perhaps around having read 200 stories – I lost a bit of interest in my online writers groups. There were new cliques on the island, and going through all that "making friends" thing again seemed a little tiresome. One of those friends, the English novelist Laura Denham, was based in San Francisco, and in a nice twist, when she moved back to London to live, she was the first person I'd met online that I later met in real life. We're still in touch.

The possibility of the web, as a writer, was there from almost the first time I logged in. A year or so before Blogger, I was posting my own online writers diary (using Frontpage Express), and had some of my stories online. The web also inspired my work. I wrote an ongoing satire about this new culture, called "Where do you want to go today?" purloining Microsoft's current advertising campaign, which today reads like a list of dot com memes.

I've blogged about literature online for best part of a decade; have seen how online magazines are now as respected as print ones (and with a much wider readership); and have replaced photocopying my magazine with perfect bound books from Lulu.com.

Strangely though, despite the internet's present ubiquity, and the move to mobile, it was that first wonderfully communal experience of the Zoetrope online writers' group that I still remember so fondly. The possibilities were there from the start, and we're only just beginning to come to grips with them.

Adrian Slatcher blogs about literature at artoffiction.blogspot.com his website is www.adrianslatcher.com. He works for Manchester Digital Development Agency managing European projects, and frequently advises the arts about how best to use technology.

19 March, 2012

07 March, 2012

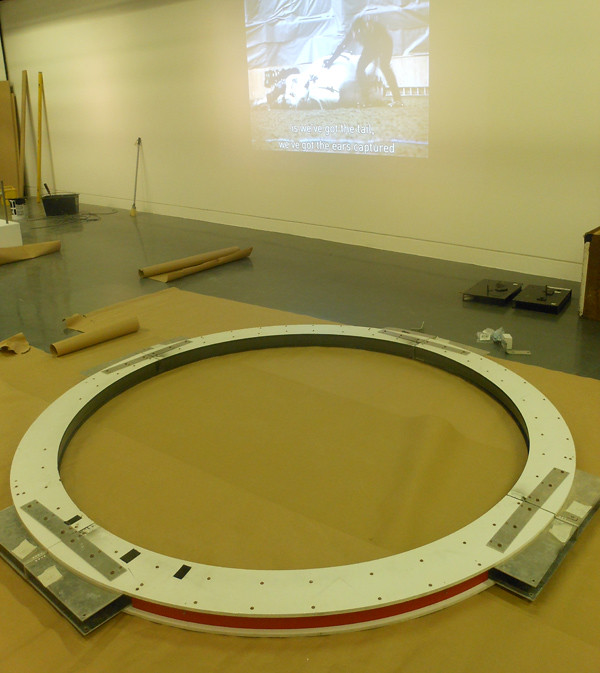

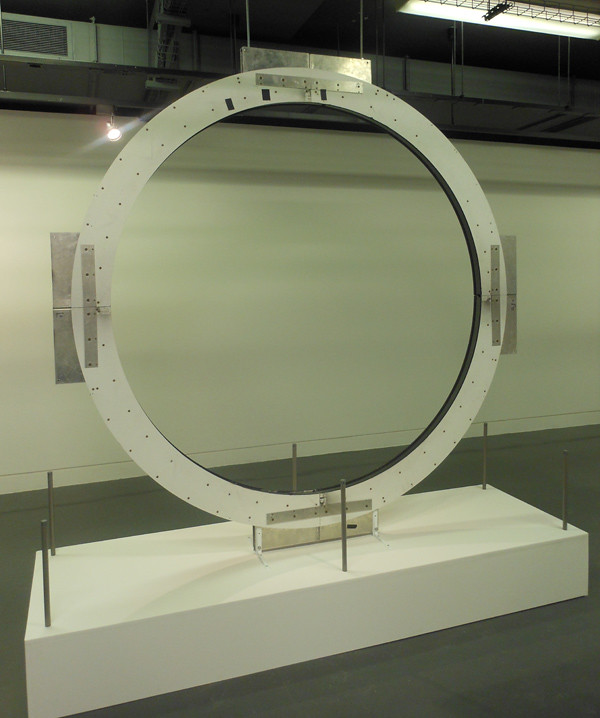

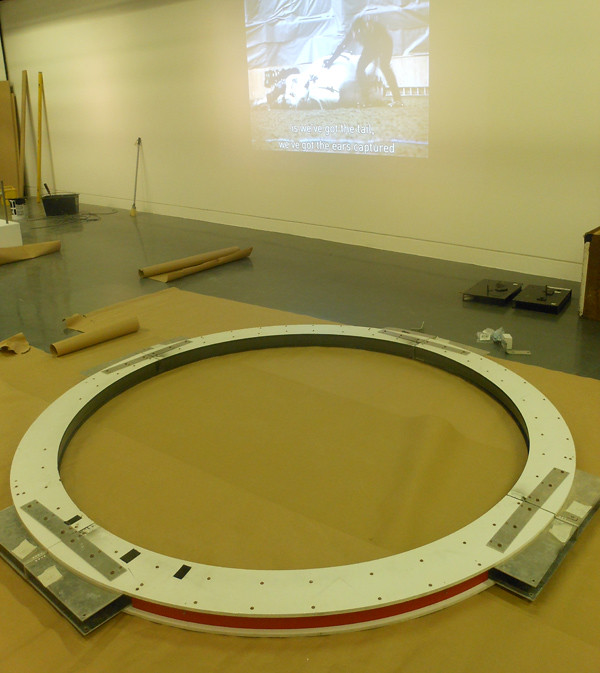

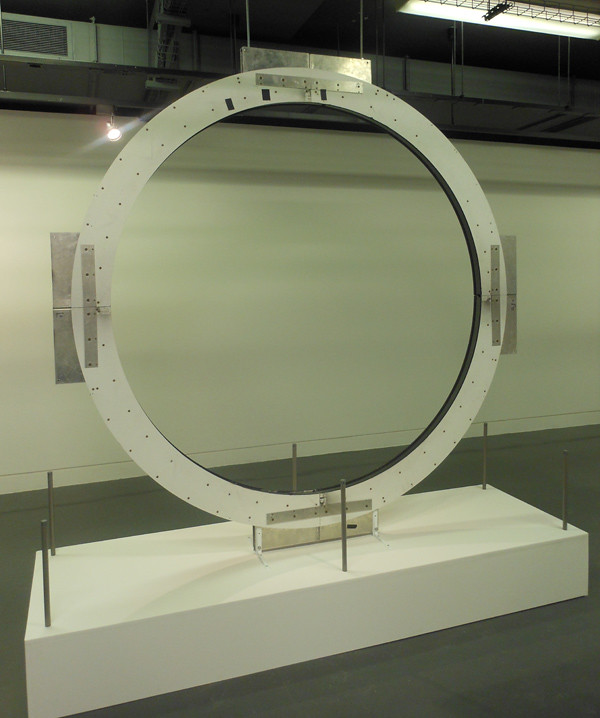

In the Blink of an Eye: Installing a Timeslice

Blogger: Beth Hughes, Exhibitions Assistant

Installing a new exhibition involves facing many challenges - it's not all just hanging pictures on a wall - and today we tackled quite a challenge. As part of our forthcoming exhibition, In the Blink of an Eye: Media and Movement, we will be displaying a Timeslice.

A Timeslice is a large ring with a series of cameras facing into the centre of the circle. When an object passes through the circle, all the cameras simultaneously take a picture. When shown in sequence it seems as if the camera can pan around and see every angle of whatever has passed through the Timeslice. The object is frozen in time and space. This technology is widely used in both television and film, most notably in the Matrix films.

The Timeslice can take hundreds of images capturing one moment in time. Unlike a normal camera, there aren't any lenses or shutters, just a single strip of film around the inside. When an object passes through the circle a flash goes off exposing the film through a series of tiny pinholes. This means that the images have to be taken in the dark to ensure no early exposure.

Although not too heavy, the Timeslice is a tricky item to handle. Standing at eight feet in diameter, it took five of our best employees to safely install and secure it.

The Timeslice on display was donated to the Museum by Tim Macmillan who pioneered the technology in the 1990s. This will be the first time we have displayed it in the Museum, but it had a starring role on an episode of Tomorrow's World in May 1993.

In the Blink of an Eye reveals our fascination with movement and our desire to capture it through photography, film, television and new media. The exhibition is on display in Galleries 1 and 2 from 9 March – 2 September 2012.

Installing a new exhibition involves facing many challenges - it's not all just hanging pictures on a wall - and today we tackled quite a challenge. As part of our forthcoming exhibition, In the Blink of an Eye: Media and Movement, we will be displaying a Timeslice.

A Timeslice is a large ring with a series of cameras facing into the centre of the circle. When an object passes through the circle, all the cameras simultaneously take a picture. When shown in sequence it seems as if the camera can pan around and see every angle of whatever has passed through the Timeslice. The object is frozen in time and space. This technology is widely used in both television and film, most notably in the Matrix films.

The Timeslice can take hundreds of images capturing one moment in time. Unlike a normal camera, there aren't any lenses or shutters, just a single strip of film around the inside. When an object passes through the circle a flash goes off exposing the film through a series of tiny pinholes. This means that the images have to be taken in the dark to ensure no early exposure.

Although not too heavy, the Timeslice is a tricky item to handle. Standing at eight feet in diameter, it took five of our best employees to safely install and secure it.

The Timeslice on display was donated to the Museum by Tim Macmillan who pioneered the technology in the 1990s. This will be the first time we have displayed it in the Museum, but it had a starring role on an episode of Tomorrow's World in May 1993.

In the Blink of an Eye reveals our fascination with movement and our desire to capture it through photography, film, television and new media. The exhibition is on display in Galleries 1 and 2 from 9 March – 2 September 2012.

Labels:

beth hughes,

cultural olympiad,

exhibition,

imove,

in the blink of an eye,

movement,

photography,

timeslice

Location:

Bradford, West Yorkshire, UK

05 March, 2012

How we test the Life Online gallery exhibits

Blogger: Catherine Elvin, Audience Researcher and Advocate

My role in the Life Online team is to find out how our visitors react to each element of the galleries, and to look for ways that we can improve their experiences. I go out and talk to our audiences, with the aim of discovering what they find interesting and engaging, and what might be confusing or difficult to understand.

One of the best things about my role is that I get to work with everybody on the team, and see how things are progressing with all areas of the project, from the exhibitions and galleries to the websites and workshops.

One of the largest areas of work for Life Online has been testing the new interactive exhibits with visitors. I've been involved all the way along in developing these exhibits, and my team are currently doing some testing with working prototypes.

For the Life Online gallery, all the interactive exhibits are touch-screen, computer-based exhibits. They look at very different elements of the history and use of the internet; how the internet has replaced older technologies; what the early web looked like; how online businesses have succeeded and failed. The prototypes aren't always finished exhibits - usually we'll be wheeling a computer around on a trolley - sometimes it will just be an idea explained using a slide show or on paper.

We ask visitors to have a go at the exhibit, and imagine they've just encountered it in a gallery, then we ask some questions to ascertain what they particularly liked about it and which bits still need work. When we've collected a range of different opinions about the exhibit, we talk to the design team about what they can do to improve the exhibit based on that feedback. This can be anything from making the key messages clearer, to changing where buttons are on the screen to make a game more intuitive to play.

We've nearly finished working on the interactive exhibits, and it's exciting to see everything coming together as we get closer to the final install date.

My role in the Life Online team is to find out how our visitors react to each element of the galleries, and to look for ways that we can improve their experiences. I go out and talk to our audiences, with the aim of discovering what they find interesting and engaging, and what might be confusing or difficult to understand.

One of the best things about my role is that I get to work with everybody on the team, and see how things are progressing with all areas of the project, from the exhibitions and galleries to the websites and workshops.

One of the largest areas of work for Life Online has been testing the new interactive exhibits with visitors. I've been involved all the way along in developing these exhibits, and my team are currently doing some testing with working prototypes.

For the Life Online gallery, all the interactive exhibits are touch-screen, computer-based exhibits. They look at very different elements of the history and use of the internet; how the internet has replaced older technologies; what the early web looked like; how online businesses have succeeded and failed. The prototypes aren't always finished exhibits - usually we'll be wheeling a computer around on a trolley - sometimes it will just be an idea explained using a slide show or on paper.

We ask visitors to have a go at the exhibit, and imagine they've just encountered it in a gallery, then we ask some questions to ascertain what they particularly liked about it and which bits still need work. When we've collected a range of different opinions about the exhibit, we talk to the design team about what they can do to improve the exhibit based on that feedback. This can be anything from making the key messages clearer, to changing where buttons are on the screen to make a game more intuitive to play.

We've nearly finished working on the interactive exhibits, and it's exciting to see everything coming together as we get closer to the final install date.

Labels:

audience testing,

catherine elvin,

galleries,

interactives,

life online

Location:

Bradford, West Yorkshire, UK

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)